The Case of the Fluorescent Fibers

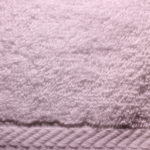

NIGHTSEA founder Charles Mazel was in his Orlando, Florida, hotel room while in town for a conference when he decided to do what he often does when curiosity strikes – look for fluorescence. Armed with a blue light and yellow barrier filter glasses, he didn’t have to look long before he came upon a curiosity – brightly fluorescent ‘spots’ in a standard issue hotel towel.

Curious (and perhaps a bit worried) he decided to take a closer look. It did not look like any kind of ‘objectionable’ contamination, but rather discrete material, perhaps fibers. And it made for pretty pictures.

(Click any image for larger view)

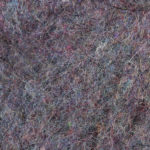

- Hotel towel under white light

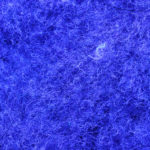

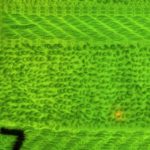

- Hotel towel under blue light

From a previous exploration (see this blog post), Charlie knew that brightly fluorescent fibers routinely show up in dryer lint.

- Dryer lint – dark load, white light

- Dryer lint – dark load, ultraviolet fluorescence

- Dryer lint – dark load, blue light fluorescence

We decided to explore the towel question a little further. Together with new hire James Garner we started out with two hypotheses to test:

H1: Towels are made from recycled material from mixed sources and fluorescent fibers are incorporated as an integral part of the towel during the manufacturing process.

H2: New towels are free of fluorescent fibers and pick them up by transfer from other textiles in the washing/drying process.

We ordered a set of white washcloths. If there were no fluorescent spots in these brand-new washcloths it would suggest that Hypothesis 1 was incorrect, and we would then investigate if fluorescent fibers could be introduced during a wash cycle (Hypothesis 2).

It was clear immediately that there were fluorescent spots even in these brand-new washcloths. Below are pictures of the fresh washcloths under white light and under blue light with barrier filter:

- Factory fresh wash cloth under white light

- Factory fresh wash cloth under blue light

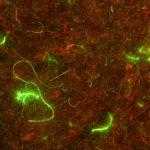

Voila! Fluorescent spots present. Hypothesis 1 confirmed, right? Well, no. Upon inspection under the microscope it became clear that the fluorescence was not coming from fibers woven into the washcloth itself – the fluorescent fibers are extraneous. See the pictures below, taken with a stereo microscope outfitted with the NIGHTSEA SFA:

- Wash cloth under white light

- Fluorescent fiber under blue light

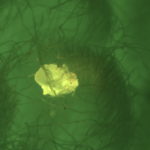

So, the fluorescent fibers are contaminants, not a part of the washcloth itself. In addition, we found other flecks of unknown fluorescent material, as shown below:

- Unknown ‘fleck’ under white light

- Unknown ‘fleck’ under blue light

These additional observations seem to rule out H1: If the material was made with the fluorescent fibers we would expect to see the fibers woven into the washcloth itself. The fluorescent entities we found were all incidental, or not fibers at all.

At this point we had to introduce a new hypothesis – H3: the fluorescent fibers are not part of the initial stages of manufacture, but are picked up before they go out the door. This could happen if the product is washed and dried in machines that are also used for fabrics that do include fluorescent fibers.

To confirm that transfer could take place, whether at the original manufacturer or in routine washing afterwards, we washed and dried washcloths under two treatments. For treatment 1 a new washcloth (marked A) was thrown in with James’s dirty clothes and detergent using cold water. For treatment 2 another new cloth (B) was washed by itself. The washcloths were marked in quadrants before washing to facilitate comparison. Fluorescent spots were counted before and after washing to see if there was a quantifiable difference, and images were made to document the results.

Both of the washcloths had fluorescent fibers on them before going through the washing and drying process, and both had an increased number of fluorescent fibers along with non-fluorescent extraneous fibers/lint. Washcloth A had only 3 fluorescent entities on it before going through treatment. Afterwards it had 19. Washcloth B had 4 fluorescent entities on it pre-treatment and 30 after. It is clear that at least James’s washer and/or dryer add, distribute, and redistribute fluorescent fibers and particles.

- Quadrant A1 before: white light

- Quadrant A1 before: blue light

- Quadrant A1 before: zoomed in on circle, blue light

- Quadrant A7 before: white light

- Quadrant A7 before: blue light

- Quadrant A7 after: white light

- Quadrant A7 after: blue light

- Quadrant B8 before: white light

- Quadrant B8 before: blue light

- Quadrant B8 after: white light

- Quadrant B8 after: blue light

- Microscope image of quadrant B8 after wash/dry: white light

- Microscope image of quadrant B8 after wash/dry: blue light

- Microscope image of fluorescent fiber from quadrant B8 after wash/dry: white light

- Fluorescent fiber under blue light

- Fluorescent fiber from quadrant A7 after wash/dry: white light

- Fluorescent fiber from quadrant A7 after wash/dry: blue light

The results suggest that the hypothesis that fibers are acquired in the wash/dry process is the correct one. This transfer is analogous to the well-known Locard’s exchange principle, the fundamental idea behind trace evidence examination in forensics. This principle says that the perpetrator of a crime brings something into the crime scene and leaves with something from it, and that both can be used as forensic evidence. So in addition to picking up fluorescent fibers, it is likely that the washcloths and towels leave something of themselves behind in each wash/dry cycle. Fortunately there are no victims in this exchange 🙂

We still don’t know enough about how these washcloths were manufactured, processed and handled to draw any concrete conclusions on the origin of the original fluorescent materials. However, our evidence supports our third hypothesis – that the fluorescent fibers on the new products are not part of the initial stages of manufacture, but are picked up before they go out the door. Based on this very small-scale investigation, it’s easy to imagine how a towel or washcloth, being washed and dried repeatedly over the course of its life, could collect a large number of fluorescent fibers. Enough so that when Dr. Charles Mazel used his fluorescence imaging gear to look at his hotel room, his attention would be drawn directly to the interesting fluorescent spots.

This just goes to show – something as simple as a fluorescing towel in a hotel room can lead down a path to discovery and intrigue. It demonstrates the value of fluorescence as a tool for investigation, and that fluorescence can be used to visualize the beauty all around us – especially in unexpected places!